Dealing With Hunger in the Midst of Plenty: Stories of Change

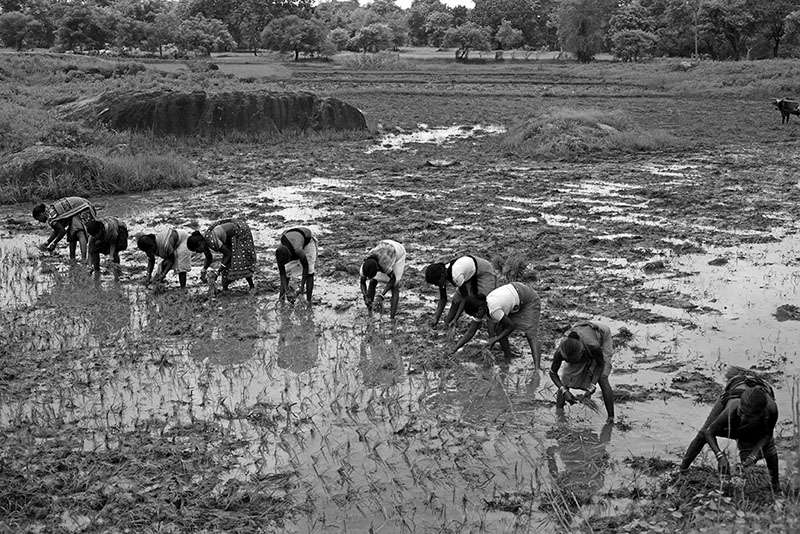

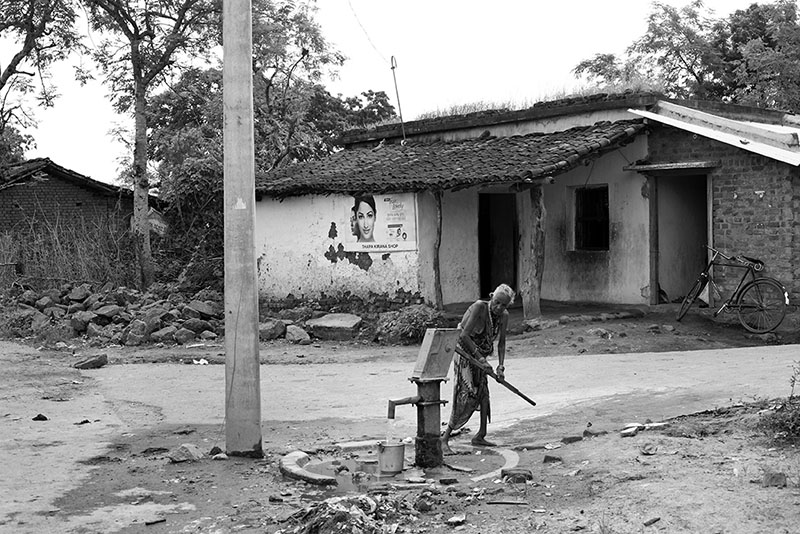

Tracks of verdant green forests, washed in the intermittent rains of mid-August and sparkling, lush paddy standing in fields of water greeted us as we drove to Padampur sub-division of Bargarh district of Western Odisha to look at a movement that had been working for food security in one of the poorest regions of the country.

Seeing our astonishment at the greenery, Kailash Chandra Nayak, activist from Samuhik Marudi Pratikar Udyam Padampur (SMPUP) pointed out that this had been an unusual year for drought-prone Padampur, which had such heavy rains that there were floods in late July and people had to be evacuated.

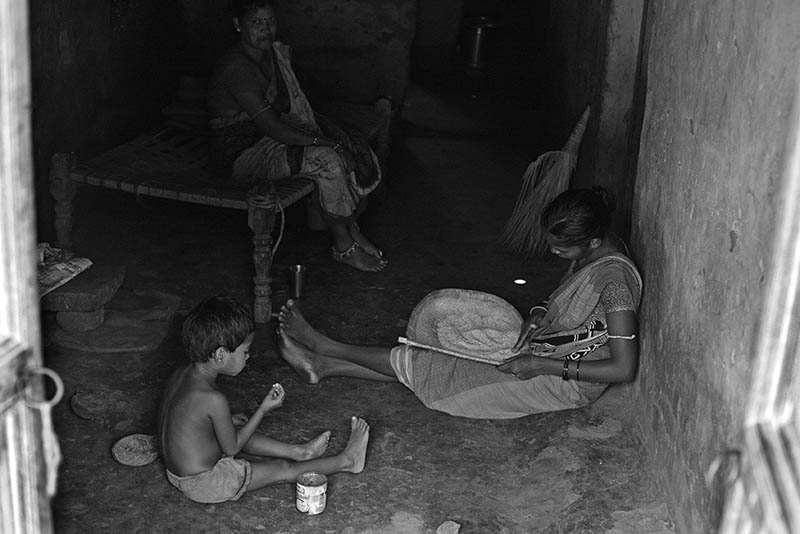

Though adjoining the Hirakud dam, the Padampur block gets no water from it and is dependent on the rains for agriculture, leading to massive migration of the landless dalits and scheduled tribes. Ironically, not too far away, in the same Bargarh district, is the Attabira block, irrigated round the year and known as Odisha’s rice bowl because of the exemplary paddy production.

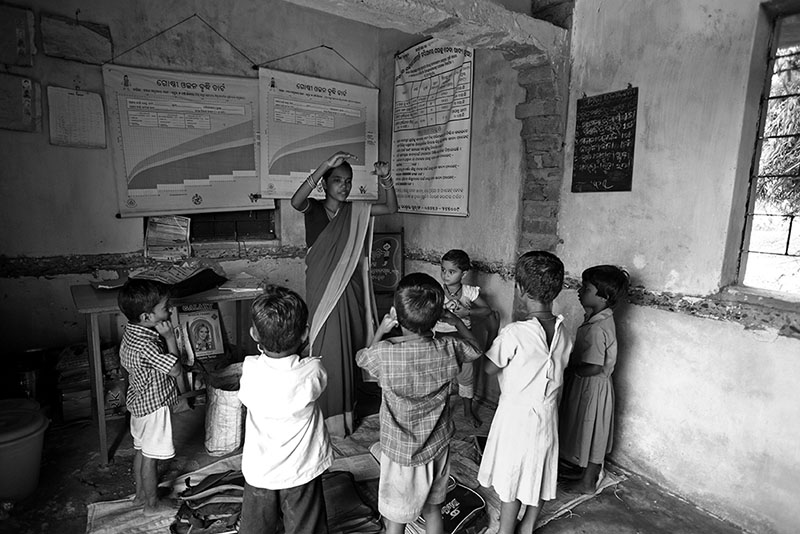

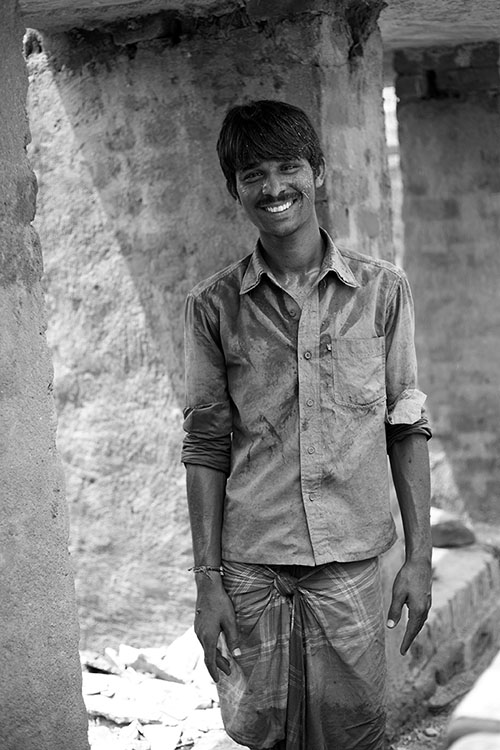

Padampur a drought-prone region was so far removed from modern development that it seemed to belong to an- other planet. Yet it was serene, peaceful and yes, free of plastics and garbage dumps. There was positive energy in the people and you could see the impact of eight years of sustained work in energizing people through a movement. Land for landless, a home of their own, accessing the government ordained rights and entitlements for those living below the poverty line had reduced migration and improved people’s lives. Organic farming was being practiced and it was wonderful to see streams of girls going to school on their pink cycles, their hair neatly braided looking clean and confident.

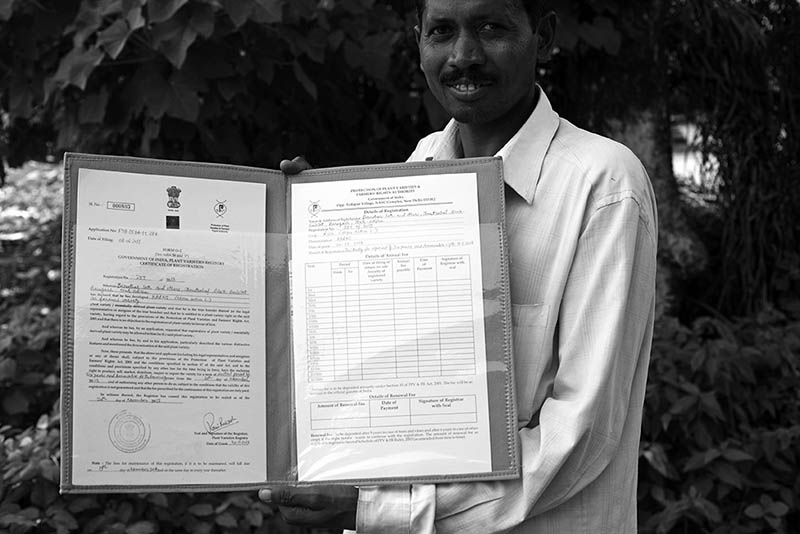

The collective surge for peoples’ entitlements was spearheaded by Samuhik Marudi Pratikar Udyam Padampur (SMPUP) and supported by community based organizations. In 107 of the poorest villages, the challenge was to tackle the perennial hunger and this was done by working on the community’s right to food. In fact a Right to Information (RTI) was led to find out entitlements of the poor in the back- ward, drought-prone area and thus began the struggle to get the 25 kg rice a month as the allocation as against the 16 kg they were getting once in two/three months.

A ‘Fight Fund’ was launched with each member of the community contributing a rupee a month and 250 grams of grain which was set aside for the struggle. As more members joined the movement, the contributions swelled. Micro plans were drawn for each village; the large number of landless identified the poverty levels established as the first steps to check migration. Women’s participation in forestry enhanced, so did their fee for collecting bundles of kendu leaves from 16 paise for a bundle of 20 to 60 paise. Women assumed leadership roles as keepers of traditional seeds, improving health care, procuring land records and fighting alcoholism, the last with the support of youth.

As against labour migrating for work, today youth who have completed schooling are going to the metros, improving skills and finding jobs in factories and garment units. They are the golden boys bringing money and status to the villages.

Padampur sub-division of Bargarh district of Western Odisha, India.

Text by: Usha Rai